Today we’d like to introduce you to Gonzalo Pozo.

Today we’d like to introduce you to Gonzalo Pozo.

Gonzalo, we appreciate you taking the time to share your story with us today. Where does your story begin?

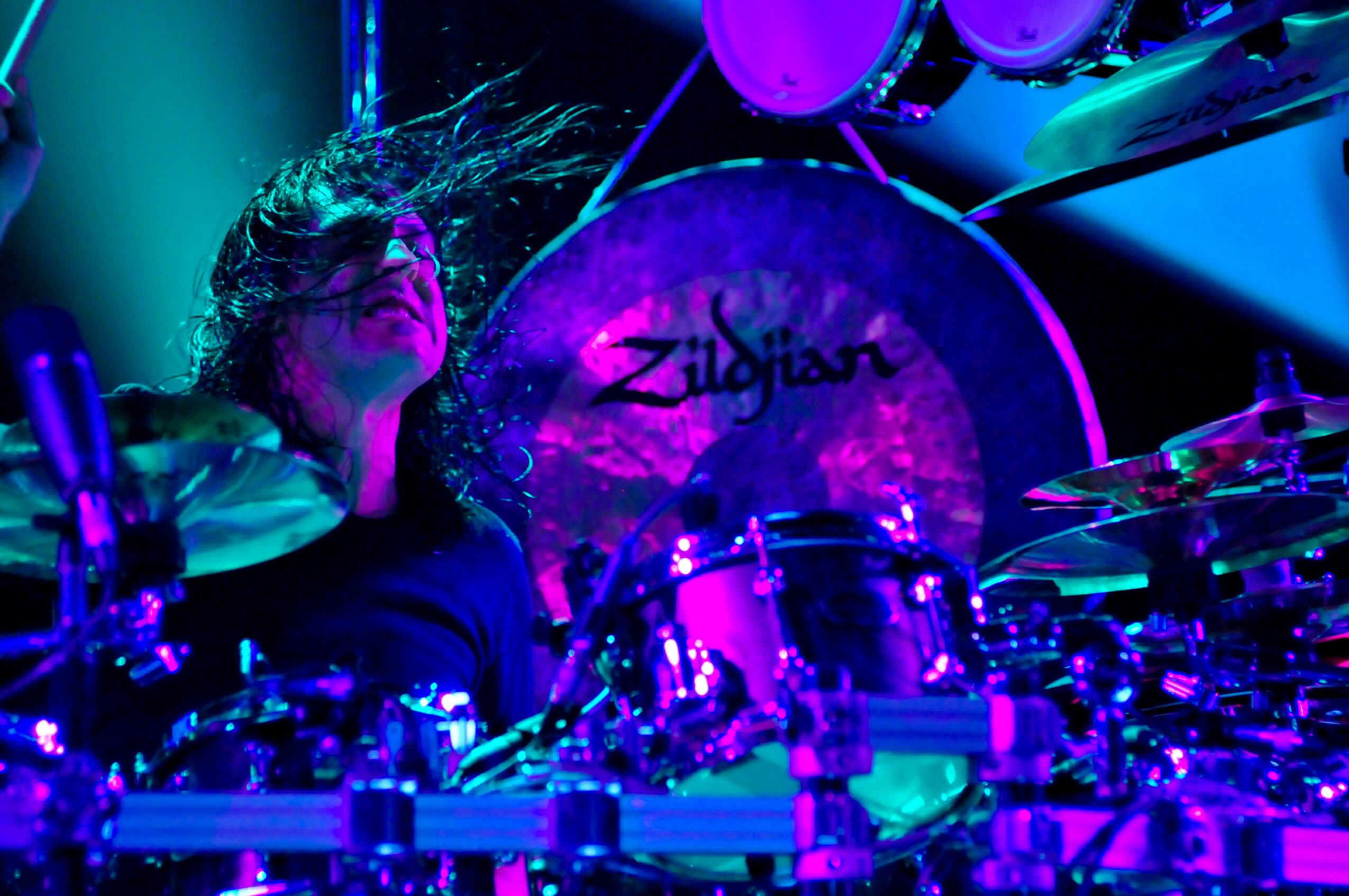

I started dabbling in photography by sneaking single-use cameras into concerts in the late 90s.

That rarely turned up anything worthwhile, and I wasted a lot of money processing bad exposures and making bad prints of those bad exposures, but I enjoyed the hell out of doing it and it got me on course.

I also contributed to a number of metal zines and websites across Texas, Pennsylvania, and Washington state around this time, and I was soon able to acquire the coveted photo pass, which would not only allow me to bring a camera into a show but also guarantee me a spot right in front of the stage in many cases.

I soon found myself with a third-hand Minolta SLR and a beater 50mm lens. Even though I had access to this cool thing called the Internet and the wealth of knowledge it offers, I continued making the same dumb mistakes and wasting tons more on film and processing. I eventually learned how to make a mediocre picture; occasionally, I’d even take a decent one.

An up-and-coming cable-access show called The Scene approached me about handling their website in late 2004, and I was soon taking live concert photos for them as well.

This allowed me to shoot much bigger artists at much bigger venues than before: Among my first assignments for them were Slayer and Billy Idol, but the first frame I took for them that still makes me proud seventeen years later was a shot of King Diamond at Sunset Station that I took between prison bars that were set up at the edge of the stage. 50mm, f/1.7, 1/60, and Fuji Superia 1600 press film, which had surprisingly fine-grain compared to other slower film stocks. I used that film for shots I still have in my portfolio of System of a Down, Judas Priest, and others.

I’d also become a dad by this point, and I went through plenty of films photographing my child and my friends’ children. This served me pretty well when I was approached about doing family and school photography several years later. It was also around this time that I became a student of off-camera flash, or OCF, through the books of one Joe McNally.

With his insights, I learned how artificial light can be manipulated to create whole moods, and a sea of possibilities opened up. Having gone digital by this point made re-learning photography much, much easier. The Hot-Shoe Diaries literally changed how I view the world around me.

Before long, I was introduced to urban exploration, steel wool spins, and a few years later, real estate. I should have expected it, but learning real estate photography did wonders for my urbex and urban landscape shooting, at both the camera and the computer.

I’d also started fusing everything I’d learned just to keep things interesting. For example, I took a long exposure sibling portrait of two kids with their feet dangling over the San Antonio river with a steel wool spin going at the camera right. The kids themselves were lit with a gelled three-flash bracket through an umbrella. It’s a simple idea, but I love the result.

More recently, I’ve learned how to temper my tendency to get carried away with OCF, corrective gels, funky depth-of-field, and so on. I love doing all that weird experimental shit, but many times the simplest approach yields the most powerful results.

With roughly two decades of learning under my belt, I absolutely see a difference between the natural light portraits I’ve taken recently versus the ones I did back when I started.

We all face challenges, but looking back would you describe it as a relatively smooth road?

I tend to get fixated on one particular aspect of the photographic process.

Editing, needlessly complex lighting, and so on. These are obviously valuable skills that I’ll try to improve as long as I continue to shoot, but I’ve gotten better at stepping back and looking at the whole picture, so to speak.

Having a broad vocabulary is not a good reason to use fifty words when five will do.

Can you tell our readers more about what you do and what you think sets you apart from others?

Most of my photography work is in real estate. I’ve had the privilege of working with a number of agents who primarily deal in luxury properties, so I’ve shot many thoughtfully designed homes.

I particularly enjoy doing twilight shoots, where the exterior shots are taken shortly after sunset when the skies are a pale blue or purple, but it’s not yet dark. I do this with all the window shades open and all the lights on to make the home look alive. I especially love doing this with homes that have large windows, great landscaping with great lighting, and pools.

I’ve started approaching urban landscapes this way. One photo I quite love was taken from the Koehler garage at the Pearl, facing south towards the food hall with the downtown San Antonio skyline in the distance, using a 24mm tilt-shift lens. The intended use of a tilt-shift lens is to correct the converging vertical lines one gets when angling a lens upward, but in this case, I used it for the bizarre depth of field it offers.

The foreground, background, and edges of the photo are a dreamy blur, but the food hall and the skyline are in sharp focus, even though they’re about two miles away from each other. This effect cannot be achieved in-camera with a conventional lens.

The funky depth of field, the pallid blue-pink skies, the warm glow of the lighting, and the “miniature model” perspective the tilt-shift can give all come together to make the most striking urban landscape photo I’ve ever taken.

I’ve also tracked my growth as a photographer by sporadically visiting a statue of an angel at the University of the Incarnate Word. My most recent photo of this guy was also taken around dusk with my tilt-shift lens. I’d been experimenting with that lens around the campus, and I just happened to pass him as I was leaving.

The partially-lit western sky peeked beautifully from behind the trees, and I was able to position the stadium light behind the statue. A driver just happened to turn towards me as I was exposing, and that turned out to be the icing on the cake.

The afterglow in the background, the muted foreground, the halo effect behind the statue, the glimmer of the headlights, and the bizarro depth of field all convene without overpowering each other. I could stare at this photo for hours.

What matters most to you? Why?

The appearance of simplicity. That’s the true hallmark of thoughtful design.

Contact Info:

- Website: www.thephotoninja.net

- Instagram: instagram.com/thephotoninjasa

- Facebook: facebook.com/thephotoninjasa